Home > Media News >

Source: http://www.niemanlab.org/

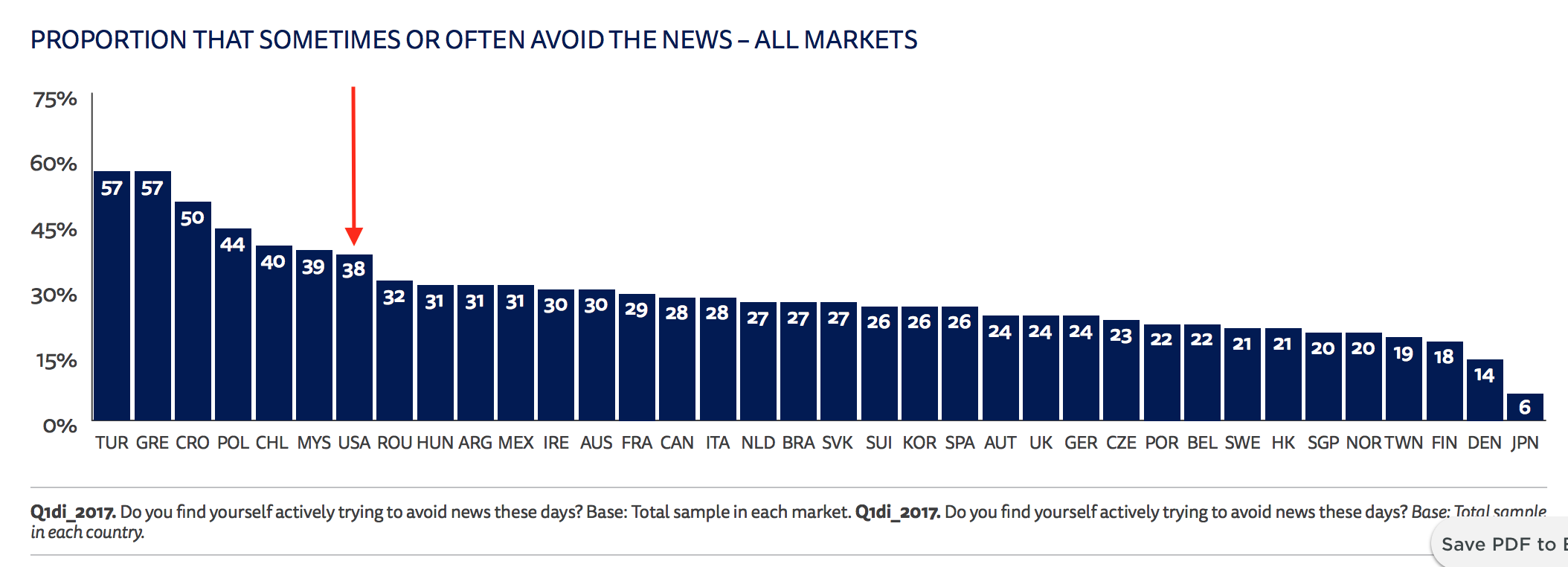

People might prefer to avoid news altogether. In its annual Digital News Report released this past June, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism looked at news avoidance, “the extent to which people find themselves actively avoiding the news.” It differs by country; the authors suggest that “economic and political turmoil…may be a contributory factor to high levels of avoidance,” though “it is not easy to identify a clear pattern,” and more than a third of U.S. respondents said they found themselves actively trying to avoid the news. This puts us in company with Poland, Chile, and Malaysia, and not so far from Turkey and Greece.

As Reuters notes, there are various reasons for news avoidance: “avoidance stemming from the depressing nature of the content itself, and avoidance due to disapproval of the news media more broadly.” In the U.S., Reuters found, readers on the left were more likely to avoid news than readers on the right; 57 percent of U.S. respondents said their main reason for avoiding news was that “it can have a negative effect on my mood,” compared to the 35 percent who said “I can’t find news to be true.”

Whatever the reason, news avoidance goes hand in hand with many of our overarching concerns about fake news. When times are bad, some people tune out for emotional self-preservation; others find comfort in sources that align with their political orientation. Many (self included) do a bit of both.

Related: News fatigue, which ProPublica’s Ariana Tobin writes about here. “What if we chose to ask for our readers’ attention only — and I mean only — when we had something new to say? I’m talking about raising the bar on sending the seventh tweet promoting the same story, commissioning an extra Facebook video that autoplays a point everyone already knows, or pushing the same alert as every other competitor in the market,” she writes.

Meanwhile, The Daily Beast’s Taylor Lorenz writes about how exhausted consumers will “abandon posting on open social networks and instead spend more time in closed networks and group chats…As users migrate to these closed systems, they’re also shifting away from the type of broad-based algorithmic feeds packed with news and media content that were the hallmark of first-generation social media.”

If we indeed see a trend of people hunkering down and tuning out, a lot of the concern about fake news on social media platforms becomes less relevant. At the same time, the acceleration of the existing trend of people cloistering themselves in like-minded groups isn’t particularly reassuring, either.

— Users will be given more tools to customize their feeds, predicts the Berkman-Klein Center’s Sara M. Watson; they’ll “be able to subscribe to filters, trusted curators who overlay onto the standard feed-filtering algorithms. Picture user interfaces with new levers for control. What’s the balance between news articles and friend updates you want in your feed this week? Want to filter out all Trump news for the day? Stop showing me prankster videos. Subscribe to only show me AP-verified news in my feed…Imagine being able to mute all men in your feed for just a few hours at a time! Or cutting back on ‘rudeness’ or sensationalism in your feed.”

But I can also easily imagine a darker flip side of this: A filter that blocks content from any outlet Trump has called fake news, one that mutes anything written by women or people of color, one that only shows news that Facebook’s fact-checkers have flagged as suspect. Your news feed, as curated by The Daily Stormer…

On Friday, Facebook took steps toward this with a new “Snooze” feature for News Feed. It will roll out over the next week and will “give you the option to temporarily unfollow a person, Page or group for 30 days.” You could, for instance, block out a relative with different political views than yours for the 30 days leading up to an election (though A) you already had the option to unfollow them and B) Facebook’s algorithm is likely preventing many of their posts from appearing in your feed anyway).

— “2018 could be the year that we refactor media literacy,” writes Mike Caulfield, head of the Digital Polarization Initiative at the American Democracy Project. Yes, he says, we’ll certainly see more media literacy initiatives — “there will be 32 headlines that claim a newly funded company has ‘solved the information literacy problem,’ all dutifully transcribed from the latest Y Combinator press releases” — but what if instead we try to find something that actually works?

Because, as Will Sommer, author of the Right Richter newsletter on right-wing media, notes:

I hope 2018 is the year that media prognosticators stop hoping that ‘media literacy’ programs will educate away the problem of people falling for obvious hoaxes in their news.

Anyone who would actually seek out media literacy training doesn’t need it, and Republican legislators would never allow a school curriculum that advised against trusting, say, Infowars.

My favorite research of the year, from Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew at Stanford, focused on how bad even smart people are at evaluating sources online. Wineburg suggests a different type of media literacy training, one that focuses on heuristics rather than wishy-washy “is it fake news?” checklists, and I’m excited to see more on this in 2018. (He’s done some work with Caulfield, whom I cited above.)

— In “Moving fake news research out of the lab,” Poynter’s Alexios Mantzarlis writes about the stream of fake news research published this year; I attempted to distill some of it in this column, but know I still missed a lot. “2017 saw a lot of new research in this space, to the point where the International Fact-Checking Network is launching a research database to catalog the most interesting academic findings. But it’s still not enough to help practitioners do a better job,” Mantzarlis writes. The one thing he really wants to happen: Facebook to open up its data.

Cross-country collaboration against Facebook. Axel Springer, the largest digital publisher in Europe, became the first non-American publisher to joined the U.S. trade association News Media Alliance, Hadas Goldreported for CNN. “For us, it’s a new beginning of working on political matters in the United States,” said Dietrich von Klaeden, Axel Springer’s SVP for public affairs.

The target: Facebook and Google. “Frankly it plays to Google and Facebook’s advantage in particular that we are all in our cubby holes and talking only about European or U.S. business, but in reality they’re international problems,” said News Media Alliance president David Chavern.

The cross-country alliance could allow publishers to better fight Facebook and Google on the digital advertising side, but it’s also interesting at a time when U.S. legislators are much more willing than they once were to regulate giant tech companies and might take cues from Europe on how to do so.

Still, the question remains what this regulation will look like; as The New York Times’ Farhad Manjoo wrote this week:

What if Facebook finds that offering people a less polarized News Feed dramatically reduces engagement on its site, affecting its bottom line? Or what if the changes disproportionately affect one political ideology over another — would Facebook stick with a kind of responsibility that risks calling into question its impartiality?

Please don’t make me stop using the term “fake news.” Poynter’s Daniel Funke — whose beat is “fact-checking, online misinformation and fake news” — covers the debate from a “growing group of media experts who say journalists should stop using ‘fake news’ — that the phrase has been too weaponized to be useful.” First Draft’s Claire Wardle and The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan “both say people should stop using the term altogether in order to prevent its further distortion, and that journalists have an obligation to use words that are more specific to the problem at hand, such as misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda.”

PolitiFact’s Aaron Sharockman, though, says the term “accurately describes a movement and a category of misinformation today that captures the public’s attention,” and compares it to how “Obamacare” was used as a pejorative by the right before being reclaimed by the left. (David Cameron appears to agree with Sharockman: “Let me put it like this, President Trump: fake news is not broadcasters criticizing you, it’s Russian bots and trolls targeting your democracy — pumping out untrue stories day after day, night after night. When you misappropriate the term fake news, you are deflecting attention from real abuses.”)

FWIW, I personally love the idea of reclaiming “fake news” from dictatorsand will continue using the term to describe the entire movement, while being more specific whenever possible.

Right Now

18 Jul, 2025 / 09:39 AM

Uber to invest 300 million-dollar in EV maker Lucid as part of robotaxi deal

21 Jul, 2025 / 08:40 AM

Google’s AI can now call local businesses to check prices and availability on your behalf

Top Stories