Home > Media News >

Source: http://www.esquire.com

Four companies dominate our daily lives unlike any other in human history: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. We love our nifty phones and just-a-click-away services, but these behemoths enjoy unfettered economic domination and hoard riches on a scale not seen since the monopolies of the gilded age. The only logical conclusion? We must bust up big tech.

I've benefited enormously from big tech. Prophet, the consulting firm I cofounded in 1992, helped companies navigate a new landscape being reshaped by Google. Red Envelope, the upscale e-commerce company I cofounded in 1997, never would have made it out of the crib if Amazon hadn’t ignited the market’s interest in e-commerce. More recently, L2, which I founded in 2010, was born from the mobile and social waves as companies needed a way to benchmark their performance on new platforms.

The benefits of big tech have accrued for me on another level as well. In my investment portfolio, the appreciation of Amazon and Apple stock restored economic security to my household after being run over in the Great Recession. Finally, Amazon is now the largest recruiter of students from the brand-strategy and digital-marketing courses I teach at NYU Stern School of Business. These firms have been great partners, clients, investments, and recruiters. And the sum of two decades of experience with, and study of, these companies leads me to a singular conclusion: It’s time to break up big tech.

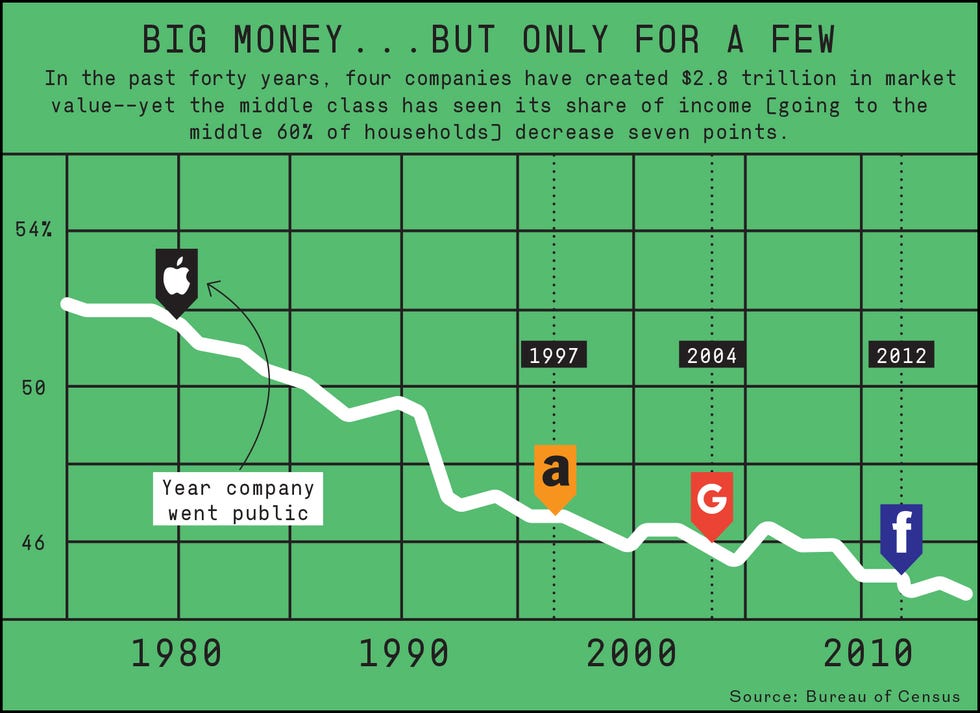

Over the past decade, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google—or, as I call them, “the Four”—have aggregated more economic value and influence than nearly any other commercial entity in history. Together, they have a market capitalization of $2.8 trillion (the GDP of France), a staggering 24 percent share of the S&P 500 Top 50, close to the value of every stock traded on the Nasdaq in 2001.

How big are they? Consider that Amazon, with a market cap of $591 billion, is worth more to the stock market than Walmart, Costco, T. J. Maxx, Target, Ross, Best Buy, Ulta, Kohl’s, Nordstrom, Macy’s, Bed Bath & Beyond, Saks/Lord & Taylor, Dillard’s, JCPenney, and Sears combined.

Meanwhile, Facebook and Google (now known as Alphabet) are together worth $1.3 trillion. You could merge the world’s top five advertising agencies (WPP, Omnicom, Publicis, IPG, and Dentsu) with five major media companies (Disney, Time Warner, 21st Century Fox, CBS, and Viacom) and still need to add five major communications companies (AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, Charter, and Dish) to get only 90 percent of what Google and Facebook are worth together.

And what of Apple? With a market cap of nearly $900 billion, Apple is the most valuable public company. Even more remarkable is that the company registers profit margins of 32 percent, closer to luxury brands Hermès (35 percent) and Ferrari (29 percent) than peers in electronics. In 2016, Apple brought in $46 billion in profits, a haul larger than that of any other American company, including JPMorgan Chase, Johnson & Johnson, and Wells Fargo. What’s more, Apple’s profits were greater than the revenues of either Coca- Cola or Facebook. This quarter, it will clock nearly twice the profits that Amazon has produced in its history.

The Four’s wealth and influence are staggering. How did we get here?

As I wrote in my book, The Four, the only way to build a company with the dominance and mass influence of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple is to appeal to a core human organ that makes adoption of the platform instinctive.

GOOGLE: MIND-ALTERING

Our brains are sophisticated enough to ask very complex questions but not sophisticated enough to answer them. Since Homo sapiens emerged from caves, we’ve relied on prayer to address that gap: We lift our gaze to the heavens, send up a question, and wait for a response from a more intelligent being. “Will my kid be all right?” “Who might attack us?”

As Western nations become wealthier, organized religion plays a smaller role in our lives. But the void between questions and answers remains, creating an opportunity. As more and more people become alienated from traditional religion, we look to Google as our immediate, all-knowing oracle of answers from trivial to profound. Google is our modern-day god. Google appeals to the brain, offering knowledge to everyone, regardless of background or education level. If you have a smartphone or an Internet connection, your prayers will always be answered: “Will my kid be all right?” “Symptoms and treatment of croup. . .” “Who might attack us?” “Nations with active nuclear-weapons programs . . .”

Think back on every fear, every hope, every desire you’ve confessed to Google’s search box and then ask yourself: Is there any entity you’ve trusted more with your secrets? Does anybody know you better than Google?

FACEBOOK: THE HEART OF THE MATTER

Facebook appeals to the heart. Feeling loved is the key to well-being. Studies of kids in Romanian orphanages who had stunted physical and mental development found that the delay was due not to poor nutrition, as suspected, but to lack of human affection. Yet one of the traits of our species is that we need to love nearly as much as we need to be loved. Susan Pinker, a developmental psychologist, studied the Italian island of Sardinia, where centenarians are six times as common as they are on mainland Italy and ten times as common as in North America. Pinker discovered that among genetic and lifestyle factors, the Sardinians’ emphasis on close personal relationships and face-to-face interactions is the key to their superlongevity. Other studies have also found that the deciding factor in longevity isn’t genetics but lifestyle, especially the strength of our social bonds.

Facebook gives its 2.1 billion monthly active users tools to fuel our need to love others. It’s satisfying to rediscover someone we went to high school with. It’s good to know we can keep in touch with friends who move away. It takes minutes, with a “like” on a baby pic or a brief comment on a friend’s heartfelt post, to reinforce friendships and family relationships that are important to us.

AMAZON: ALWAYS CONSUMING

What sight is to the eyes and sound is to the ears, the feeling of more, of insatiety, is to the gut. We crave more stuff psychologically just as the stomach craves more sugar, more carbs, after an indulgent meal. Originally this instinct operated in the service of self-preservation: Having too little meant starvation and certain death, whereas too much was rare, a bloat or a hangover. But open your closets or your cupboards right now, and you’ll probably find you have ten to a hundred times as much as you need. Rationally, we know this makes no sense, but society and our higher brain haven’t caught up to the instinct of always feeling like we need more.

Amazon is the large intestine of the consumptive self. It stores nutrients and distributes them to the cardiovascular system of the 64 percent of American households who are Prime members. It has adopted the best strategy in the history of business—“more for less”—and deployed it more effectively and efficiently than any other firm in history.

APPLE: SET TO VIBRATE

The second-most-powerful instinct after survival is procreation. As sexual creatures, we want to signal how elegant, smart, and creative we are. We want to signal power. Sex is irrational, luxury is irrational, and Apple learned very early on that it could appeal to our need to be desirable—and in turn increase its profit margins—by placing print ads in Vogue, having supermodels at product launches, and building physical stores as glass temples to the brand.

A Dell computer may be powerful and fast, but it doesn’t indicate membership in the innovation class as a MacBook Air does. Likewise, the iPhone is something more than a phone, or even a smartphone. Consumers aren’t paying $1,000 for an iPhone X because they’re passionate about facial recognition. They’re signaling they make a good living, appreciate the arts, and have disposable income. It’s a sign to others: If you mate with me, your kids are more likely to survive than if you mate with someone carrying an Android phone. After all, iPhone users on average earn 40 percent more than Android users. Mating with someone who is on the iOS platform is a shorter path to a better life. The brain, the heart, the large intestine, and the groin: By appealing to these four organs, the Four have entrenched their services, products, and operating systems deeply into our psyches. They’ve made us more discerning, more demanding consumers. And what’s good for the consumer is good for society, right?

Well, yes and no. The Four have so much power over our lives that most of us would be rocked to the core if one or more of them were to disappear. Imagine not being able to have an iPhone, or having to use Yahoo or Bing for search, or losing years’ worth of memories you’ve posted on Facebook. What if you could no longer order something with one click on the Amazon app and have it arrive tomorrow?

At the same time, we’ve handed over so much of our lives to a few Silicon Valley executives that we’ve started talking about the downsides of these firms. As the Four have become increasingly dominant, a murmur of concern—and even resentment—has begun to make itself heard. After years of hype, we’ve finally begun to consider the suggestion that the government, or someone, ought to put the brakes on.

Not all of the arguments are equally persuasive, but they’re worth restating before we get to the real reason I believe we ought to break up big tech.

Big tech learned from the sins of the original gangster, Microsoft. The colossus at times appeared to feel it was above trafficking in PR campaigns and lobbyists to soften its image among the public and regulators. In contrast, the Four promote an image of youth and idealism, coupled with evangelizing the world-saving potential of technology.

The sentiment is sincere, but mostly canny. By appealing to something loftier than mere profit, the Four are able to satisfy a growing demand among employees for so-called purpose-driven firms. Big tech’s tinkerer- in-the-garage mythology taps into an old American reverence for science and engineering, one that dates back to the Manhattan Project and the Apollo program. Best of all, the companies’ vague, high-minded pronouncements—“Think Different,” “Don’t Be Evil”—provide the ultimate illusion. Political progressives are generally viewed as well-meaning but weak, an image that offered the perfect cover for companies that were becoming hugely powerful.

Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg told women to “lean in” because she meant it, but she also had to register the irony of her message of female empowerment, set against a company that emerged from a site originally designed to rank the attractiveness of Harvard undergraduates, much less a firm destroying tens of thousands of jobs in an industry that hires a relatively high number of female employees: media and communications.

These public-relations efforts paid off handsomely but also set the companies up for a major fall. It’s an enormous letdown to discover that the guy who seems like the perfect gentleman is in fact addicted to opioids and a jerk to his mother. It’s even worse to learn that he only hung out with you because of your money (clicks).

In my experience as the founder of several early Internet firms, the people who work for the Four are no more or less evil than people at other successful companies. They’re a bit more educated, a little smarter, and much luckier, but like their parents before them, most are just trying to find their way and make a living. Sure, many of them would be happy to help out humanity. But presented with the choice between the betterment of society or a Tesla, most would opt for the Tesla—and the Tesla dealerships in Palo Alto are doing well, really well. Does this make them evil? Of course not. It simply makes them employees at a for-profit firm operating in a capitalist society.

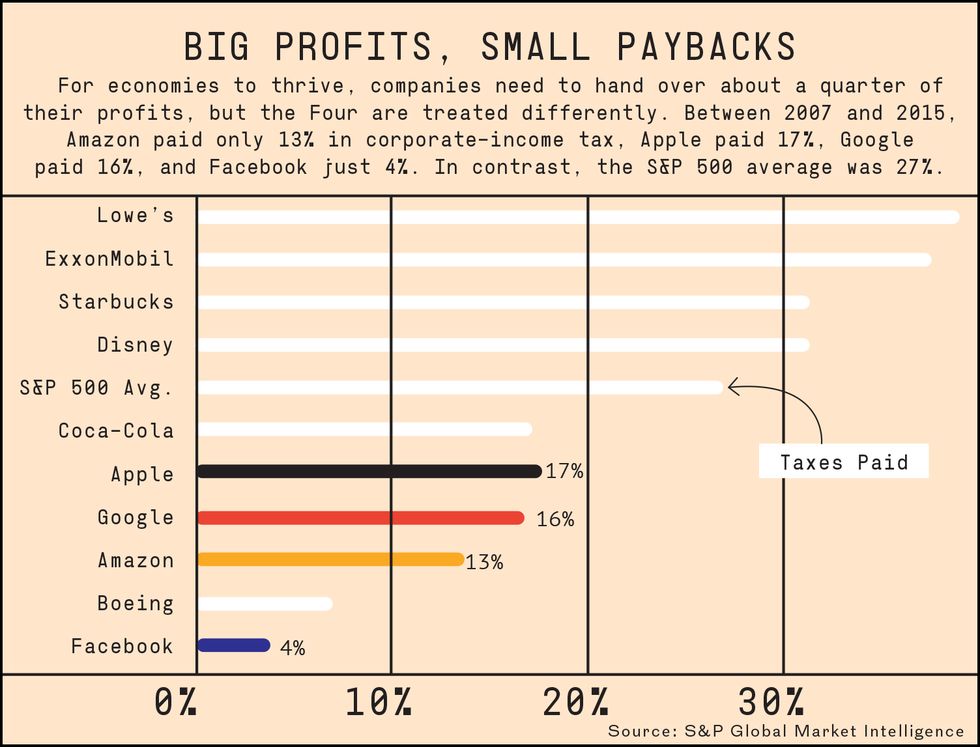

Our government operates on an annual budget of approximately 21 percent of GDP, money that is used to keep our parks open and our military armed. Does big tech pay its fair share? Most would say no. Between 2007 and 2015, Amazon paid only 13 percent of its profits in taxes, Apple paid 17 percent, Google paid 16 percent, and Facebook paid just 4 percent. In contrast, the average tax rate for the S&P 500 was 27 percent.

So, yes, the Four do avoid taxes . . . and so do you. They’re just better at it. Apple, for example, uses an accounting trick to move its profits to domains such as Ireland, which results in lower taxes for the most profitable firm in the world. As of September 2017, the company was holding $250 billion overseas, a hoard that is barely taxed and should never have been abroad in the first place. That means a U. S. company is holding enough cash overseas to buy Disney and Netflix.

Apple is hardly alone. General Electric also engages in massive tax avoidance, but we’re not as angry about it, as we aren’t in love with GE. The fault here lies with us, and with our democratically elected government. We need to simplify the tax code—complex rules tend to favor those who can afford to take advantage of them—and we need to elect officials who will enforce it.

The destruction of jobs by the Four is significant, even frightening. Facebook and Google likely added $29 billion in revenue in 2017. To execute and service this additional business, they will create twenty thousand new, high-paying jobs.

The other side of the coin is less shiny. Advertising—whether digital or analog—is a low-growth (increasingly flat) business, meaning that the sector is largely zero-sum. Google doesn’t earn an extra dollar by growing the market; it takes a dollar from another firm. If we use the five largest media-services firms (WPP, Omnicom, Publicis, IPG, and Dentsu) as a proxy for their industry, we can estimate that $29 billion in revenue would have required about 219,000 traditional advertising professionals to service. That translates to 199,000 creative directors, copywriters, and agency executives deciding to “spend more time with their families” each year—nearly four Yankee Stadiums filled with people dressed in black holding pink slips.

The economic success stories of yesterday employed many more people than the firms that dominate the headlines today. Procter & Gamble, after a run-up in its stock price in 2017, has a market capitalization of $233 billion and employs ninety-five thousand people, or $2.4 million per employee. Intel, a new-economy firm that could be more efficient with its capital, enjoys a market cap of $209 billion and employs 102,000 people, or $2.1 million per employee. Meanwhile, Facebook, which was founded fourteen years ago, boasts a $542 billion market cap and employs only twenty-three thousand people, or $23.4 million per employee—ten times that of P&G and Intel.

Granted, we’ve seen job destruction before. But we’ve never seen companies quite this good at it. Uber set a new (low) bar with $68 billion spread across only twelve thousand employees, or $5.7 million per employee. It’s hardly obvious that a ride-share company—which requires actual drivers on the actual roads—would be the one to arbitrage the middle class with a Houdini move that would have Henry Ford spinning in his grave.

But Uber managed it by creating a two-class workforce, complete with a new classification: “driver-partners,” in other words, contractors. Keeping them off the payroll means that Uber’s investors and twelve thousand white-collar employees do not share any of the company’s $68 billion in equity with its “partners.” In addition, the firm is not inconvenienced with paying health or unemployment insurance and paid time off for any of its two-million-strong driver workforce.

Big tech’s job destruction makes an even stronger case for getting these firms to pay their fair share of taxes, so that the government can soften the blow with retraining and social services. We should be careful, however, not to let job destruction be the lone catalyst for intervention. Job replacement and productivity improvements—from farmers to factory workers, and factory workers to service workers, and service workers to tech workers—are part of the story of American innovation. It’s important to let our freaks of success fly their flag.

Getting warmer. Having your firm weaponized by foreign adversaries to undermine our democratic election process is bad . . . really bad. During the 2016 election, Russian troll pages on Facebook paid to promote approximately three thousand political ads. Fabricated content reached 126 million users. It doesn’t stop there—the GRU, the Russian military-intelligence agency, has lately taken a more bipartisan approach to sowing chaos. Even after the election, the GRU has used Facebook, Google, and Twitter to foment racially motivated violence. The platforms invested little or no money or effort to prevent it. The GRU purchased Facebook ads in rubles: literally and figuratively a red flag.

If you’re a country club with a beach or a pool, it’s more profitable, in the short run, not to have lifeguards. There are risks to that business model, as there are to Facebook’s dependence on mainly algorithmic moderation, but it saves a lot of money. The notion that we can expect big tech to allocate the requisite resources, of the companies’ own will, for the social good is similar to the idea that Exxon will take a leadership position on global warming. It’s not going to happen.

However, the alarm for trust busting, not just regulation, rang for me in November, when Senate Intelligence Committee chairman Richard Burr pleaded with the general counsels of Facebook, Google, and Twitter, “Don’t let nation-states disrupt our future. You’re the front line of defense for it.” This represented a seminal moment in our history, when our elected officials handed over our national defense to firms whose business model is to nag you about the shoes you almost bought, and remind you of your friends’ birthdays.

They should be our front line against our enemies?

Let’s be clear, our front line of defense has been, and must continue to be, the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines. Not the Zuck.

It’s not just federal officials who have folded in the face of big tech. As part of their bid for Amazon’s second headquarters, state and city officials in Chicago proposed to let Amazon keep $1.3 billion in employee payroll taxes and spend this money as the company sees fit. That’s right: Chicago offered to transfer its tax authority to Amazon and trusts the Seattle firm to allocate taxes in a manner best for Chicago’s residents.

The surrender of our government only gets worse from there. If you want to manufacture and sell a Popsicle to children, you must undergo numerous expensive FDA tests and provide thorough labeling that outlines the ingredients, calories, and sugar content of the treat. But what warning labels are included in Instagram’s user agreement? We’ve now seen abundant research indicating that social- media platforms are making teens more depressed. Ask yourself: If ice cream were making teens more prone to suicide, would we shrug and seat the CEO of Dreyer’s next to the president at dinners in Silicon Valley?

Anyone who doesn’t believe these products are the delivery systems for tobacco- like addiction has never separated a seven- year-old from an iPad in exchange for a look that communicates a plot to kill you. If you don’t believe in the addictive aspects of these platforms, ask yourself why American teenagers are spending an average of five hours a day glued to their Internet- connected screens. The variable rewards of social media keep us checking our notifications as though they were slot machines, and research has shown that children and teens are particularly sensitive to the dopamine cravings these platforms foster. It’s no accident that many tech companies’ execs are on the record saying they don’t give their kids access to these devices.

All of these are valid concerns. But none of them alone, or together, is enough to justify breaking up big tech. The following are reasons I believe the Four should be broken up.

The Purpose of an Economy

Ganesh Sitaraman, professor at Vanderbilt Law School, argues that the U. S. needs the middle class, that the Constitution was designed for a balanced share of wealth for our representative democracy to work. If the rich have too much power, it can lead to an oligarchy. If the poor have too much power, it can lead to a revolution. So the middle class needs to be the rudder that steers American democracy on an even keel.

I believe that the primary purpose of the economy, and one of its key agents, the firm, is to create and sustain the middle class. The U. S. middle class from 1941 to 2000 was one of the most ferocious sources of good in world history. The American middle class financed, fought, and won good wars; took care of the aged; funded a cure for polio; put men on the moon; and showed the rest of the world that self-interest, and the consumption and innovation it inspired, could be an engine for social and economic transformation.

The upward spiral of an economy depends on the circular flow between households and companies. Households offer resources and labor, and companies offer goods and jobs. Competition motivates the invention and distribution of better offerings (happy hour, rear-view camera, etc.), and the big wheel spins round and round. Big tech creates enormous stakeholder value. So why are we witnessing, for the first time in decades, other countries grow their middle class while ours is declining? If an economy is meant to sustain a middle class, and the social stability it fosters, then our economy is failing.

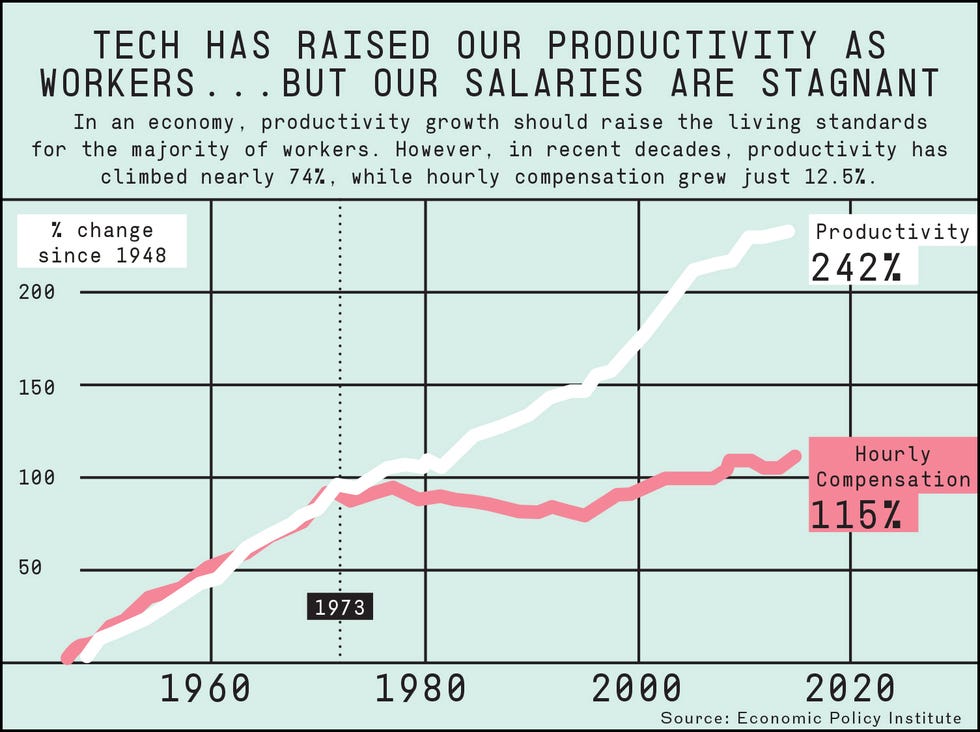

Without a doubt, there have been tremendous gains in productivity in the U. S. over the past thirty years. It would be hard to deny that the American consumer, at every level, has become the envy of the free world. Yet the productivity boost and the elevation of the consumer to modern-day nobility have created a dystopia in which we’ve traded well- paying jobs and economic security for powerful phones and coconut water delivered in under an hour.

How did that happen? Since the turn of the millennium, firms and investors have fallen in love with companies whose ability to replace humans with technology has enabled rapid growth and outsize profit margins. Those huge profits attract cheap capital and render the rest of the sector flaccid. Old-economy firms and fledgling start-ups have no shot.

The result is a winner-takes-all economy, both for companies and for people. Society is bifurcating into those who are part of the innovation economy (lords) and those who aren’t (serfs). One great idea will make a twenty- something the darling of venture capital, while those who are average, or even just unlucky (most of us), have to work much harder to save for retirement.

It’s never been easier to be a billionaire or harder to be a millionaire. It’s painfully clear that the invisible hand, for the past three decades, has been screwing the middle class. For the first time since the Great Depression, a thirty-year-old is less well-off than his or her parents at thirty.

Should we care? What if these icons of innovation are the disrupters we need to keep our economy fit? Isn’t there a chance we’ll come through the other end of the tunnel with a stronger economy and higher wages? Already there’s evidence that this isn’t happening. In fact, the bifurcation effect seems to be gaining momentum. It’s likely the biggest threat to our society. Many will argue it’s the world we live in. But isn’t the world what we make of it? And we have consciously shifted the mission of the U. S. from producing millions of millionaires to producing one trillionaire. Alexa, is this a good thing?

Markets Are Failing, Everywhere

Right now we are in the midst of a dramatic market failure, one in which the government has been lulled by the public’s fascination with big tech. Robust markets are efficient and powerful, yet just as football games don’t work without referees who regularly step in, throw flags, and move one team backward or forward, unfettered capitalism gave us climate change, the mortgage crisis, and U. S. health care.

Monopolies themselves aren’t always illegal, or even undesirable. Natural monopolies exist where it makes sense to have one firm achieve the requisite scale to invest and offer services at a reasonable price. But the tradeoff is heavy regulation. Florida Power & Light serves ten million people; its parent company, NextEra Energy, has a market cap of $72 billion. However, pricing and service standards are regulated by people who are fiduciaries for the public.

The Four, by contrast, have managed to preserve their monopoly-like powers without heavy regulation. I describe their power as “monopoly-like,” since, with the possible exception of Apple, they have not used their power to do the one thing that most economists would describe as the whole point of assembling a monopoly, which is to raise prices for consumers.

Nevertheless, the Four’s exploitation of our knee-jerk antipathy to big government has been so effective that it’s led most of us to forget that competition—no less than private property, wage labor, voluntary exchange, and a price system—is one of the indispensable cylinders of the capitalist engine. Their massive size and unchecked power have throttled competitive markets and kept the economy from doing its job—namely, to promote a vibrant middle class.

Air Supply

How do they do it? It’s useful here to remember how Microsoft killed Netscape in the 1990s. The process starts innocently enough, as a firm builds an outstanding product (Windows) that becomes a portal to an entire sector—what we’d now call a platform. To sustain its growth, the company points the portal at its own products (Internet Explorer) and bullies its partners (Dell) to shut out the competition. Even though Netscape had the more popular browser, with over 90 percent market share, it couldn’t compete with Microsoft’s implicit subsidies for Internet Explorer.

It’s happening everywhere across the Four, whether it’s the slow takeover of the entire first page of search results that Google can better monetize, substandard products on your iPhone’s home screen (like Apple Music), coordinating all assets of the firm (Facebook) to arrest and destroy a threat (Snap), or information-age steel dumping via fulfillment build-out and predatory pricing no other firm can access the capital to match (Amazon).

(Un)Natural Monopolies

Maybe the consumer is better off with these “natural” monopolies. The Department of Justice didn’t think so. In 1998, the federal government filed suit against Microsoft, alleging anticompetitive practices. During the trial, one witness reported that Microsoft executives had said they wanted to “cut off Netscape’s air supply” by giving away Internet Explorer for free.

In November 1999, a district court found that Microsoft had violated antitrust laws and subsequently ordered the company to be broken into two. (One company would sell Windows; the other would sell applications for Windows.) The breakup order was overruled by an appeals court, and ultimately Microsoft agreed to a settlement with the government that sought to curb the company’s monopolistic practices by less stringent means.

The settlement was criticized by some for being too lenient, but it’s worth asking whether Google—today worth $770 billion and the object of affection for any free-market evangelist—would exist if the DOJ hadn’t put Microsoft on notice regarding the infanticide of promising upstarts. In the absence of the antitrust case, Microsoft likely would have leveraged its market dominance to favor Bing over Google, just as it had used Windows to euthanize Netscape.

Indeed, the DOJ’s case against Microsoft may have been one of the most market-oxygenating acts in business history, one that unleashed trillions of dollars in shareholder value. The concentration of power achieved by the Four has created a market desperate for oxygen. I’ve sat in dozens of VC pitches by small firms. The narrative has become universal and static: “We don’t compete directly with the Four but would be great acquisition candidates.” Companies thread this needle or are denied the requisite oxygen (capital) to survive infancy. IPOs and the number of VC-funded firms have been in steady decline over the past few years.

Unlike Microsoft, which was typecast early on as the “Evil Empire,” Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon have combined savvy public-relations efforts with sophisticated political lobbying operations—think Oprah Winfrey crossed with the Koch brothers—to make themselves nearly immune to the scrutiny endured by Microsoft.

The Four’s unchecked power manifests most often as a restraint of competition. Consider: Amazon has become such a dominant force that it’s now able to perform Jedi mind tricks and inflict pain on potential competitors before it enters the market. Consumer stocks used to trade on two key signals: the underlying performance of the firm (Pottery Barn’s sales per square foot are up 10 percent) and the economic macro-climate (more housing starts). Now, however, private and public investors have added a third key signal: what Amazon may or may not do in the respective sector. Some recent examples:

The day Amazon announced it would enter the dental-supply business, dental-supply companies’ stock fell 4 to 5 percent. When Amazon reported it would sell prescription drugs, pharmacy stocks fell 3 to 5 percent.

Within twenty-four hours of the Amazon– Whole Foods acquisition announcement, large national grocery stocks fell 5 to 9 percent.

When the subject of monopolistic behavior comes up, Amazon’s public-relations team is quick to cite its favorite number: 4 percent—the share of U. S. retail (online and offline) Amazon controls, only half of Walmart’s market share. It’s a powerful defense against the call to break up the behemoth. But there are other numbers. Numbers you typically won’t see in an Amazon press release: • 34 percent: Amazon’s share of the worldwide cloud business

• 44 percent: Amazon’s share of U. S. online commerce

• 64 percent: U. S. households with Amazon Prime

• 71 percent: Amazon’s share of in-home voice devices

• $1.4 billion: Amount of U. S. corporate taxes paid by Amazon since 2008, versus $64 billion for Walmart. (Amazon has added the entire value of Walmart to its market cap in the past twenty-four months.)

What about Facebook? Eighty-five percent of the time we spend on our phones is spent using an app. Four of the top five apps globally—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger—are owned by Facebook. And the top four have allied, under the command of the Zuck, to kill the fifth—Snap Inc. What this means is that our phones are no longer communications vehicles; they’re delivery devices for Facebook, Inc.

Facebook even has an internal database that tells it when a competitive app is gaining traction with its users, so that the social network can either acquire the firm (as it did with Instagram and WhatsApp) or kill it by mimicking its features (as it’s trying to do with Stories and Bonfire, which are aimed at Snapchat and Houseparty).

Google, for its part, now commands a 92 percent share of a market, Internet search, that is worth $92.4 billion worldwide. That’s more than the entire

advertising market of any country except the U. S. Search is now a larger market than the following global industries:

• paper and forest products: $81 billion

• construction and engineering: $79 billion

• real estate management and development: $76 billion

• gas utilities: $58 billion

How would we feel if one company controlled 92 percent of the global construction and engineering trade? Or 92 percent of the world’s paper and forest products? Would we worry that their power and influence had breached a reasonable threshold, or would we just think they were awesome innovators, as we do with Google? And then there’s Apple, the most successful firm selling a low-cost product at a premium price. The total material cost for the iPhone 8 Plus is $288, a fraction of the $799 price tag.

Put another way, Apple has the profit margin of Ferrari with the production volume of Toyota. Apple’s users are among the most loyal, too. It has a 92 percent retention rate among consumers, compared with just 77 percent for Samsung users. In February 2017, 79 percent of all active iOS users had updated to the most recent software, versus just 1.2 percent of all active Android devices.

Apple uses its privileged place in consumers’ lives to instill monopoly-like powers in its approach to competitors like Spotify. In 2016, the firm denied an update to the iOS Spotify app, essentially blocking iPhone users’ access to the latest version of the music-streaming service. While Spotify has double the subscribers of Apple Music, Apple makes up the discrepancy by placing a 30 percent tax on its competition.

Apple is not shy about using its popularity among consumers to its advantage. It was recently discovered that Apple has been purposely slowing down performance on outdated iPhone models, a strategy that is likely to entice users to upgrade sooner than they would have otherwise. This is the confidence of a monopoly.

In the late nineteenth century, the term trust came into use as a way to describe big businesses that controlled the majority of a particular market. Teddy Roosevelt gained a reputation as the original “trust buster” by breaking up the beef and railroad trusts, and filing forty more antitrust suits during his presidency. Fast-forward a hundred years, to 2016, and we find candidate Trump announcing that a Trump administration would not approve the AT&T–Time Warner merger “because it’s too much concentration of power in the hands of too few.” A year later, his Justice Department sued to block it.

So our presidents are still fighting the good fight, right? Well, let’s break this down. AT&T has 139 million wireless subscribers, sixteen million Internet subscribers, and twenty-five million video subscribers, about twenty million of which were acquired from DirecTV. Time Warner owns content-producing brands such as HBO, Warner Bros., TNT, TBS, and CNN. A vertical merger between the two companies could, in theory, create a megacorporation capable of creating and distributing content across its network of millions of wireless-phone, Internet, and video subscribers.

Too much power in the hands of too few? Maybe. But if content-and-distribution heft is what we’re worried about, then Teddy would have been knocking on Jeff’s, Tim’s, Larry’s, and Mark’s doors a decade ago. Already each of the Four has content and distribution that dwarfs a combined AT&T–Time Warner:

• Amazon spent $4.5 billion on original video in 2017, second only to Netflix’s $6 billion. Prime Video has launched in more than two hundred countries and recently struck a $50 million deal with the NFL to stream ten Thursday-night games. Amazon controls a 71 percent share in voice technology and has an installed distribution base of 64 percent of American households through Prime. Name a cable company with a 64 percent market share—I’ll wait. In addition, Amazon controls more of the market in cloud computing than the next five largest competitors combined. Alexa, does this foster innovation?

• Apple is set to spend $1 billion on original content this year. The company controls 2.2 million apps and set a record in 2013 when the number of songs it sold on iTunes hit twenty- five billion. Apple’s library now includes forty million songs, which can be distributed across the company’s one billion active iOS devices, and that’s not even mentioning its television and video offerings. But AT&T needs to sell Cartoon Network?

• Facebook owns a torrent of content created by its 2.1 billion monthly active users. Through its site and its apps, the company reaches 66 percent of U. S. adults. Facebook plans to spend $1 billion on original content. It’s the world’s most prolific content machine, dominating the majority of phones worldwide. Now “what’s on your mind?”

• Four hundred hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute, which means that Google has more video content than any other entity on earth. It also controls the operating system on two billion Android devices. But AT&T needs to divest Adult Swim?

Perhaps Trump is right that the merger of AT&T and Time Warner is unreasonable, but if so, then we should have broken up the Four ten years ago. Each of the Four, after all, wields a harmful monopolistic power that leverages market dominance to restrain trade. But where is the Department of Justice? Where are the furious Trump tweets? Convinced that the guys on the other side of the door are Christlike innovators, come to save humanity with technology, we’ve allowed our government to fall asleep at the wheel.

Margrethe Vestager, the EU commissioner for competition, is the only government official in a Western country whose testicles have descended—who is not afraid of, or infatuated with, big tech. Last May, she levied a $122 million fine against Facebook for lying to the EU about its ability to share data between Facebook and WhatsApp, and a month later she penalized Google $2.7 billion for anticompetitive practices.

This was a good start, but it’s worth noting that those fines are mere mosquito bites on the backs of elephants. The Facebook fine represented 0.6 percent of the acquisition price of WhatsApp, and Google’s amounted to just 3 percent of its cash on hand. We are issuing twenty-five-cent parking tickets for not feeding a meter that costs $100 every fifteen minutes. We are telling these companies that the smart, shareholder-friendly thing to do is obvious: Break the law, lie, do whatever it takes, and then pay a (relatively) anemic fine if you happen to get caught.

The monopolistic power of big tech serves as a macho test for capitalists. The embrace of the innovation class makes us feel powerful. We like success, especially outrageous success, and we’re inspired by billionaires and the incredible companies they founded. We also have a gag reflex when it comes to regulation, one that invites unattractive labels. Since I started suggesting that Amazon should be broken up, Stuart Varney of Fox News, a charming guy, has taken to introducing me on-air as a socialist. Any day now, I suspect he’ll start calling me European.

There’s no question that the markets sent a strong signal in 2017 that our economy is sated on regulation. But there’s a difference between regulation and trust busting. What’s missing from the story we tell ourselves about the economy is that trust busting is meant to protect the health of the market. It’s the antidote to crude, ham-handed regulation. When markets fail, and they do, we need those referees on the field who will throw a yellow flag and restore order. We are so there.

The tremendous success of the Four—which alone accounted for 40 percent of the gains in the S&P 500 for the month of October—wallpapers over the fact that, as a whole, the markets in which they operate are not healthy. Late last year, Refinery29 and BuzzFeed, two promising digital-marketing fledglings, announced layoffs, while Criteo, an ad-tech firm, shed 50 percent of its market capitalization. Why? Because there is Facebook, there is Google, and then there is everyone else. And all of those other firms, including Snap Inc., are dead; they just don’t know it yet.

Are we sure all these companies deserve to die? Or is it the case that our markets are failing and preventing the development of a healthy ecosystem with dozens of digital-marketing firms growing, hiring, and innovating?

Search...Your Feelings

Imagine two markets. One that includes the firms below:

Amazon | Apple | Facebook | Google

And another that includes these independent firms:

![]()

As Darth Vader urged his son, I want you to “search your feelings” and answer which market would:

Create more jobs and shareholder value.

While trust busting is typically bad for stocks in the short run, busting up Ma Bell unleashed a torrent of shareholder growth in telecommunications. Similarly, Microsoft, despite its run-in with the DOJ in the 1990s, just hit an all-time high. In addition, it’s reasonable to believe that Amazon and Amazon Web Services may be worth more as separate firms than they are as one.

Inspire more investment.

There are half as many publicly traded U. S. firms than there were twenty-two years ago, and most firms in the innovation economy understand that their most likely—or only—path to exist is to be acquired by big tech. An absence of buyers makes for an economy in which the two options are to go big (become Google) or go home (go out of business). While home runs provide good theater, the doubles and triples of acquisitions by medium-sized firms are likely a stronger engine of growth.

Broaden the tax base.

The aggregation of power has resulted in firms that have so much political clout and resources that they can bring their effective tax rates well below what midsize companies pay, creating a regressive tax system.

Why should we break up big tech? Not because the Four are evil and we’re good. It’s because we understand that the only way to ensure competition is to sometimes cut the tops off trees, just as we did with railroads and Ma Bell. This isn’t an indictment of the Four, or retribution, but recognition that a key part of a healthy economic cycle is pruning firms when they become invasive, cause premature death, and won’t let other firms emerge. The breakup of big tech should and will happen, because we’re capitalists. It’s time.

Right Now

18 Jul, 2025 / 09:39 AM

Uber to invest 300 million-dollar in EV maker Lucid as part of robotaxi deal

21 Jul, 2025 / 08:40 AM

Google’s AI can now call local businesses to check prices and availability on your behalf

Top Stories